The average Canadian household uses 223 litres of water every day. Drinking, cooking, bathing, washingāit all adds up.

For the more than 200,000 Halifax residents served by the J.D. Kline Water Supply Plant, that water flowing through their taps and pipes comes from Pockwock Lake. Located just north of the historic African Nova Scotian community of Upper Hammonds Plains, it could easily be mistaken for just another sparkling gem in Nova Scotiaās impressive collection of waterways. Youād never think, from the scenic view, that millions of litres of that lake water are being pumped out of the lake each day to be treated, piped to residences and businesses across the municipality, and returnedāafter treatment, of courseāto start the journey all over again.

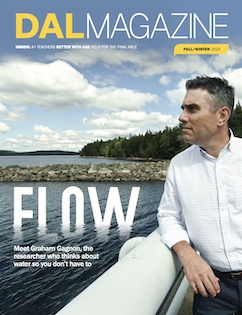

Dr. Graham Gagnon thinks about it. A lot.

āMost people donāt have to know much about where the water in their tap comes fromāthey just assume itās there,ā he explains. āWe donāt always think about it in the same way we would a bridge, or a building, but thereās a reason the water industry is filled with engineers.

Itās because the problems theyāre solving are systems problems: theyāre technical, theyāre 24/7, often expensive, and require professional judgement.ā

Foundational partnerships

Ģż

When it comes to water professionals across Atlantic Canada and beyond, Dr. Gagnon and have become not just a critical resource but a foundational partner to utilities like and the The centreās work with these organizations is longstanding and multifacetedāhardly a typical researcher-for-contract relationship.

From drinking-water safety to wastewater testing for infections like COVID-19, Dr. Gagnon and a cross-disciplinary team of researchers work every day to help solve a wide range of water-related science and technology problems.

The person at the centre of that enterprise has more than just water on his mind. Dr. Gagnon has been both a Canada Research Chair and a . Heās generated more than $50 million in research funding, co-authored more than 200 journal articles, and has been feted with major industry awards; most recently he was elected as a fellow to the prestigious . His research programs have trained over 250 studentsāalumni who now are playing leadership roles in water science and safety across Canada and globally. And though heās an engineer by trade, heās now serving as dean of Dalās Faculty of Architecture & Planning, helping to forge a stronger, more unified future for the two disciplines through the same relationship-based approach thatās defined his entire career.

Related reading:ĢżDal engineer elected fellow by the prestigious Canadian Academy of Engineering for distinguished service

āHe has an incredible ability to connect the dots that nobody else sees,ā says Dr. Wendy Krkosek (PhDā13), acting director of environmental health & safety with Halifax Water and an alum of Dr. Gagnonās lab. āWeāve been in meetings with organizations that you would not expect to have any connection with a water utility and, all of a sudden, heās found this link that connects two-and-two together and can help forge those relationships.ā

A passion sparked

Ģż

The first time Dr. Gagnon remembers thinking about our relationship with water was on the farm. He comes from an agricultural background; his dad was an āaggieā grad from the University of Guelph. And from the time he was 10 years old or so, Dr. Gagnon worked summers on his uncleās Ontario farm. It was a small operationāmostly corn, plus a few animals, such as cattle. Then, one summer, the water went bad.

āHis neighbour was improperly disposing of agricultural waste, and it contaminated all of the wells in the area,ā recalls Dr. Gagnon. āIt was the first time I understood a bit about how all these things fit together.ā

He says he finds that people who work in water almost inevitably have a story like hisāsome personal experience where what was once taken for granted suddenly becomes all-important, and the personal, practical, and policy implications spill out from there. āIt changes the discourse of a community or a business really fast when you donāt have water,ā says Dr. Gagnon.

That can be the case anytime a city or community experiences a failure in their water infrastructure or when residents are told they must boil their water before consuming it. Thankfully, most of these are short-term issuesābut there are also many communities across Canada, a large number of them remote or Indigenous communities, where water restrictions and boil orders are routine and regular, with wide-ranging and long-term impacts.

āThose types of narratives stick with me,ā says Dr. Gagnon, retelling stories of meeting local leaders struggling with community water issues. āWe live in Canada. Weāre a wealthy country. We should be able to solve drinking water problems for communities. This shouldnāt be something thatās insurmountable.ā

āWe live in Canada. Weāre a wealthy country. We should be able to solve drinking water problems for communities. "

A collaboration hub

Ģż

The Centre for Water Resources Studies was founded in the early 1980s, back when Dalās Faculty of Engineering was part of the Technical University of Nova Scotia (TUNS). Dr. Gagnon, who trained as an environmental engineer, joined the faculty at »Ź¹Ś²©²Źapp in 1998, just after the TUNS/»Ź¹Ś²©²Źapp merger. Given his research interests in water, he quickly started collaborating with the centre and, in 2010, became its director.

āThe centre has long-standing relationships with a number of partners, where we think strategically about how we collaborate over multiple years,ā he explains. āBut then there are the unexpected projects that come our way, where someone hears about something weāve done, reaches out and weāre like, āHey this could be interesting to work on.āā

Like when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, for example, and the centre collaborated with public health officials in Nova Scotia to develop a wastewater surveillance program for early and accurate detection of SARS-CoV-2. Or back in the 2000s, when the Dal Student Union sought to reduce bottled water consumption on campus and raised questions about the potential of lead traces in campus drinking water; one of Dr. Gagnonās students produced a study that guided Facilities Management in developing a robust water fountain replacement strategy, and which later informed Halifax Waterās own lead service line replacement program.

Related reading: Testing the waters: Project to detect COVID-19 early through wastewater expands across Nova Scotia

Municipal connections

Ģż

The relationship is one of the longstanding pillars of the centre. Dr. Gagnon has been working with the local utility for close to two decades now on a wide range of projects. At the moment, this includes work in areas like UV disinfection, technology replacement, and helping Halifax Water prepare for how climate change is going to affect water treatment and management in the decades to come. Just this October, Halifax Water announced that they've piloted the world's first municipal scale UV LED reactor for wastewater treatmentāconducted in partnership with Dr. Gagnon and team.

Related reading: Dal Solutions: Breakthrough poised to transform wastewater treatment worldwide

āItās a really unique partnership with Graham and with the other partners in the NSERC grant,ā says Dr. Krkosek. āItās more of an open-ended journey weāre on together, where with each five-year plan we have ideas of where we think weāre going to go, but it inevitably takes us in different directions as we adapt and plan for the future.ā

The partnership also allows students to get involved in real-world situations, notes John Eisenor (BEngā99, MAScā02), Halifax Waterās director of operations and, like Dr. Krkosek, one of Dr. Gagnonās alumni. He knows personally what that kind of experience can offer.

āI had the opportunity to work in research at the J.D. Kline plant as a student, and getting exposed to Halifax Water, getting to know the staff, it kind of solidified my desire to want to work for a water utility, and Halifax Water in particular.ā

āHe gives people leadership opportunities,ā adds Dr. Lindsay Anderson (BEngā11, MAScā13, PhDā23), also a centre alum who is now a water quality manager with Halifax Water. āHe lets people run with their ideas, helping them find the connections and interact with the partners to come up with solutions. He provides a great space for creative thinking.ā

Manda Tchonlla (BāEngā22) knows that creative space quite well: she has been an intern, a masterās student, and is now a PhD student with the Centre for Water Resources Studies. Sheās currently studying water contaminant detection technology and echoes the what the centreās alumni have to say about working with Dr. Gagnon. āHe creates an environment for me to grow,ā she says. āNo matter what stage of your career you are in, he gives you the space to become the person you want to becomeā¦ heās not trying to teach researchers to be just like him. He wants you to figure out who you can be.ā

Dr. Gagnon, right, with Dr. Lindsay Anderson, Dr. Wendy Krkosek, John Eisenor.Ģż

Indigenous connections

Ģż

That ethos of helping others figure out whatās possible lies at the heart of one of the projects Dr. Gagnon is most proud of: his collaboration with the .

Dr. Gagnon first started working with the APC in 2009 to develop a comprehensive water management strategy for the Atlantic region, one that would grow Indigenous leadership and self-determination in water services. Over time, the partnership evolved into a policy framework that, in 2022, produced an agreement to transfer water and wastewater services for 17 First Nations communities from Indigenous Services Canada to the newly formed .

In 2024, the AFNWA and »Ź¹Ś²©²Źapp received a $4.3 million investment through an NSERC Alliance- Mitacs Accelerate grantāfunds that will not only further improve the quality and sustainability of Indigenous water infrastructure but help train a new generation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous professionals for the water authorityās long-term success.

A signing ceremony held on Nov. 7, 2022 transferred ministerial responsibilities and liabilities to the AFNWA for the development and delivery of water and wastewater services to participating First Nations. (Provided photo)

āGrahamās guidance was so important to the establishment of the AFNWA,ā says Chief Wilbert Marshall of the Potlotek First Nation and current AFNWA board chair. āIn our early years, he was our principal advisor, believing that our vision was the best course of action for our communities. Now, 15 years after we first reached out for his advice, the AFNWA is operational in our communities. We have taken control of decision making from the federal government, seen increased investment in our infrastructure, and begun to see improved water quality and service.ā

āThe chiefs deserve all of the credit for advancing this project,ā says Dr. Gagnon. āIām really happy that I was able to rely on my water expertise to help provide advice and insight and steer them to different leaders in the water community to help them achieve that vision of establishing a water authority.ā

Related reading:ĢżWatershed moment: Atlantic First Nations Water Authority partners with »Ź¹Ś²©²Źapp to deliver worldāclass water treatment

James MacKinnon (BScā11, MPAā20), AFNWAās director of engagement and government relations, calls Dr. Gagnon āa dedicated listenerā who has been an integral part of the authorityās success. āHe always seemed to have time to take a phone call or a meeting to provide his advice,ā he says. āI wasnāt one of Grahamās students during my time at »Ź¹Ś²©²Źapp, but Iāve learned so much having worked closely with him these last 12 years, I feel like I was. We couldnāt have asked for a better partner to build the AFNWA.ā

Administrative leadership

Ģż

That approach to partnership and relationship-building helps explain how, more than two decades after joining the Faculty of Engineering, Dr. Gagnon found himself as dean of an entirely different faculty.

Dr. Gagnon first got a taste of university administration in 2018, when he was hired for the part-time role of associate vice-president research. It was a chance to dig into Dalās research operations from a system-wide perspective, helping solve problems and open doors for colleagues across the university. That experience made him open to considering other opportunities, which is when he was approached about the deanās role in Architecture & Planning.

The Faculty was going through some real struggles; Dr. Gagnon compares it to how many businesses and organizations found their extremes heightened amongst pandemic-era modes of working and communicating. There were tensions between the Facultyās two schools and real doubts about their shared future together.

āWe wanted someone who could look at our Faculty with fresh eyes, somebody who could bring the experience of administration from a different academic discipline,ā says Dr. Mikiko Terashima, an associate professor of planning who served on the decanal selection committee.

āI was really interested in the idea of leading a Faculty through change,ā says Dr. Gagnon. āIām not an architect or a planner, but I do know the municipal space in which both those disciplines have to operate. And my different background allows me to focus mostly on being an academic leader and asking questions that arenāt specifically about the disciplines, but more, āWhat conversations do we need to create here? How can I help support this team, these people, in advancing their ambitions?āā

He dove into the task, organizing extensive one-on-one and group engagements with faculty to try and identify the best opportunities for moving things forward. Research quickly became a key priority, and since he became dean not only has research output grown but the Faculty is now developing a new PhD program. Thereās much more work to do, and at some point, he does want to see the Facultyās leadership return to someone from within its own disciplines. But, at the moment, confidence in a shared path forward is growingāperhaps best embodied by the fact that Dr. Gagnonās initial short-term appointment has now been renewed for five more years.

āHeās got a strong enough personality to have tough conversations, but he treats everyone fairly and equally,ā says Dr. Terashima, who has since taken on the new role of associate dean, research & global relations. āItās helped us get out of that feeling of being āstuckā and to focus moreĢżon the future, on the possibilities and the positives of what we can do together.āĢż

Dr. ĆmĆ©lie Desrochers-Turgeon is a new addition to the Faculty, having just joined the School of Architecture in early 2024, and she notes the energy Dr. Gagnon has helped curate.

āBecause itās not a big Faculty, heās able to actually meet with people and be more accessible, and I think thatās served him well,ā she says. āHe shows support for early-career faculty and is genuinely interested in developing research trajectories; he wants research to serve our local community and global communities too.ā

Global issues, local impactĢż

Ģż

Water might be the ultimate example of where those perspectives meetāa locally managed resource that literally spans the entire planet. āMy environmental ethos has always been that view of āthink globally, act locally,āā says Dr. Gagnon.

Little surprise, then, that the impacts of climate change are at the top of his personal agenda when it comes to the biggest and most urgent topics in the field. āClimate change is impacting our water supply now; itās obvious and itās clear, from algal blooms to impacts on groundwater because of sea-level rise. Weāre going to have very different decisions to make around treatment, quality, and quantity than people did 50 years ago, and theyāre going to get more complex 10 or 20 years from now.ā

Related reading: What's in the water? Dal expands water surveillance projects with new funding

Then thereās population growthāa particularly pertinent topic in Nova Scotia. After stagnating for over 20 years, the provinceās population has grown by more than 130,000 since 2015, the steepest increase in generations. āItās a very positive thing for Nova Scotia,ā says Dr. Gagnon, ābut it brings challenges in many respects, including water, whether thatās straining capacity in urban centres or intensifying pressure on septic fields. As neighbouring counties grow, there will be more questions: where is the wastewater going to go? Where do I treat it? Do we need more water plants?ā

He expects there to be a lot more of those one-off calls to the Centre for Water Resources Studies in the years ahead, not to mention the deepening of their core partnerships. Heās excited, though, because he knows the ethos at the heart of what the centre doesāand so much of what he doesāholds strong.

āItās about relationships, and those relationships rely on trust,ā he says. āOur partners invest not only in the idea that we are going to do good science and come up with good ideas for the water community, but that we are going be good allies. That spirit flows through every person we have here, and itās why you see our alumni going out and doing so well in the industry. Itās because we work as a team, and we work in partnership."

This story appeared in theĢżDAL Magazine Fall 2024Ģżissue. Flip through the rest of the issue using the links below.